Kabir: 1398-1518

Notes from other sources-

Kabir ranks among the world’s greatest poets. In India, he is perhaps the most quoted author, with the exception of Tulsidas. Kabir has criticized perhaps all existing sects in India, still he is mentioned with respect by even orthodox authors. Vaishnav author Nabhadas in his Bhakta-Mal (1585) writes:

hindU turuk pramAn ramainI sabadI sAkhI

pachchhapat nahiN bachan sabahiN ke hit kI bhAkhI

[His “ramaini” “shabda” “sakhi” (sections of his “Bijak”) are accepted by Hindus and Turks alike. He spoke without discrimination for the good of all]

He lived perhaps during 1398-1448. He is thought to have lived longer than 100 years. He had enormous influence on Indian philosophy and on Hindi poetry.

His birth and death are surrounded by legends. He grew up in a Muslim weaver family, but some say he was really son of a Brahmin widow who was adopted by a childless couple. When he died, his Hindu and Muslim followers started fighting about the last rites. The legend is that when they lifted the cloth covering his body, they found flowers instead. The Muslim followers buried their half and the Hindu cremated thier half. In Maghar, his tomb and samadhi still stand side by side.

Here I quote some of his verses from his “Bijak”, from the section called “sakhi”. My translation follows the Gurumukh TIkA by Puran Sahib done perhas a century ago. He was associated with the Kabirpanthi center at Burhanpur. Kabir’s writings can be hard to translate, not only because the language is old, but Kabir’s expressions are different from what we are used to seeing.

The verses below use the term “hira” (diamond). It should be noted that during the time of Kabir, diamonds were very rare. At that time, diamonds were found only in India and nowhere else.

Bijak/Sakhi 168:

hIrA soi srAhiye

sahai ghanan kI choT

kapaT kurangI mAnavA

parakhat nikrA khot

Admire the diamond that can bear the hits of a hammer. Many deceptive preachers, when critically examined, turn out to be false.

[Here diamond is siddhanta (the basic principles or doctrine).An experienced diamond cutter can hit the diamond using a chisel so that the chips will break off as expected. A diamond because if its crystalline structure tends to break off at specific angles. Similarly the true doctrine would come out shining when it is critically examined].

Bijak/Sakhi 170:

hIrA tahaN na kholiye

jahaN kunjroN kI hAT

sahajai gaNthI bANdhike

lagiye apni bAT

Don’t open your diamonds in a vegetable market. Tie them in bundle and keep them in your heart, and go your own way.

[Don’t discuss gyan (knowledge) with those who can not understand it].

Bijak/Sakhi 171:

hIrA parA bajAr maiN

rahA chhAr lapaTAy

ketihe murakh pachi mUye

koi pArakhi liyA uThAy

A diamond was laying in the street covered with dirt. Many fools passed by.

Someone who knew diamonds picked it up.

[Those who understand gyan-siddhanta (true knowledge/principles), pause to acquire it].

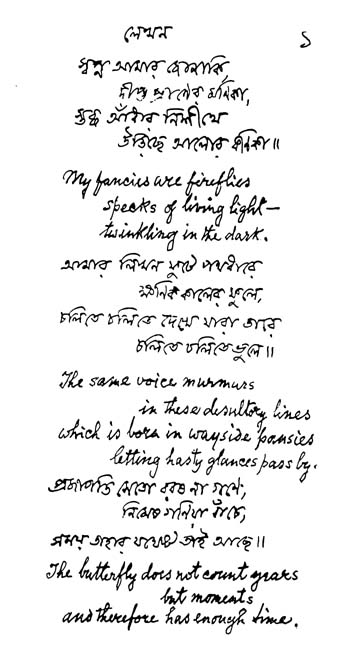

Do not go to the garden of flowers!

O friend! go not there;

In your body is the garden of flowers.

Take your seat on the thousand petals of the

lotus, and there gaze on the infinite beauty.

koi prem ki peng jhulaao re

Hang up the swing of love today!

Hang the body and the mind between the

arms of the beloved, in the ecstasy of love’s joy:

Bring the tearful streams of the rainy clouds

to your eyes, and cover your heart with

the shadow of darkness:

Bring your face nearer to his ear, and speak

of the deepest longings of your heart.

Kabir says: `Listen to me brother! bring the

vision of the Beloved in your heart.’

The following poems include some repeats from different translators:

Looking at the grinding stones,

Kabir laments

In the duel of wheels,

nothing stays intact.

Where do you search me?

I am with you

Not in pilgrimage, nor in icons

Neither in solitudes

Not in temples, nor in mosques

Neither in Kaba nor in Kailash

I am with you o man

I am with you

Not in prayers, nor in meditation

Neither in fasting

Not in yogic exercises

Neither in renunciation

Neither in the vital force nor in the body

Not even in the ethereal space

Neither in the womb of Nature

Not in the breath of the breath

Seek earnestly and discover

In but a moment of search

Says Kabir, Listen with care

Where your faith is, I am there.

O servant, where dost thou seek Me?

Lo!I am beside thee.

I am neither in temple nor in mosque:

I am neither in Kaaba nor in Kailash:

Neither am I in rites and ceremonies,

nor in Yoga and renunciation.

If thou art a true seeker, thou shalt at once see Me:

thou shalt meet Me in a moment of time.

Kabir says, “O Sadhu! God is the breath of all breath.”

*

It is needless to ask of a saint the caste to which he belongs;

For the priest, the warrior.the tradesman,

and all the thirty-six castes, alike are seeking for God.

It is but folly to ask what the caste of a saint may be;

The barber has sought God, the washerwoman, and the carpenter–

Even Raidas was a seeker after God.

The Rishi Swapacha was a tanner by caste.

Hindus and Moslems alike have achieved that End,

where remains no mark of distinction.

O friend!hope for Him whilst you live, know whilst you live,

understand whilst you live: for in life deliverance abides.

If your bonds be not broken whilst living, what hope of

deliverance in death?

It is but an empty dream, that the soul shall have union with Him

because it has passed from the body:

If He is found now, He is found then,

If not, we do but go to dwell in the City of Death.

If you have union now, you shall have it hereafter.

Bathe in the truth, know the true Guru, have faith in the trueName!

Kabir says: “It is the Spirit of the quest which helps;

I am the slave of this Spirit of the quest.”

Do not go to the garden of flowers!

O Friend! go not there;

In your body is the garden of flowers.

Take your seat on the thousand petals of the lotus,

and there gaze on the Infinite Beauty.

Tell me, Brother, how can I renounce Maya?

When I gave up the tying of ribbons, still I tied my garment about me:

When I gave up tying my garment, still I covered my body in its folds.

So, when I give up passion, I see that anger remains;

And when I renounce anger, greed is with me still;

And when greed is vanquished, pride and vainglory remain;

When the mind is detached and casts Maya away,

still it clings to the letter.

Kabir says, “Listen to me, dear Sadhu! the true path is rarely found.”

The moon shines in my body, but my blind eyes cannot see it:

The moon is within me, and so is the sun.

The unstruck drum of Eternity is sounded within me;

but my deaf ears cannot hear it.

So long as man clamors for the [?] and the [?],

his works are as naught:

When all love of the [?] is dead, then

the work of the Lord is done.

For work has no other aim than the getting of knowledge:

When that comes, then work is put away.

The flower blooms for the fruit: when the fruit comes,

the flower withers.

The musk is in the deer, but it seeks it not within itself:

it wanders in quest of grass.

When He Himself reveals Himself,

Brahma brings into manifestation

That which can never be seen.

As the seed is in the plant, as the shade is in the tree,

as the void is in the sky, as infinite forms are in the void–

So from beyond the Infinite, the Infinite comes;

and from theInfinite the finite extends.

The creature is in Brahma, and Brahma is in the creature:

they are ever distinct, yet ever united.

He Himself is the tree, the seed, and the germ.

He Himself is the flower, the fruit, and the shade.

He Himself is the sun, the light, and the lighted.

He Himself is Brahma, creature, and Maya.

He Himself is the manifold form, the infinite space;

He is the breath, the word, and the meaning.

He Himself is the limit and the limitless:

and beyond both the limited and the limitless is He,

the Pure Being.

He is the Immanent Mind in Brahma and in the creature.

The Supreme Soul is seen within the soul,

The Point is seen within the Supreme Soul,

And within the Point, the reflection is seen again.

Kabir is blest because he has this supreme vision!

Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves, and within it is the Creator: Within this vessel are the seven oceans and the unnumbered stars. The touchstone and the jewel-appraiser are within; And within this vessel the Eternal soundeth, and the spring wells up. Kabir says: “Listen to me, my Friend! My beloved Lord is within.” O How may I ever express that secret word? O how can I say He is not like this, and He is like that? If I say that He is within me, the universe is ashamed: If I say that He is without me, it is falsehood. He makes the inner and the outer worlds to be indivisibly one; The conscious and the unconscious, both are His footstools. He is neither manifest nor hidden, He is neither revealed nor unrevealed: There are no words to tell that which He is. To Thee Thou hast drawn my love, O Fakir! I was sleeping in my own chamber, and Thou didst awaken me; striking me with Thy voice, O Fakir! I was drowning in the deeps of the ocean of this world, and Thou didst save me: upholding me with Thine arm, O Fakir!Only one word and no second– and Thou hast made me tear off all my bonds, O Fakir! Kabir says, “Thou hast united Thy heart to my heart, O Fakir!”

Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves, and within it is the Creator: Within this vessel are the seven oceans and the unnumbered stars. The touchstone and the jewel-appraiser are within; And within this vessel the Eternal soundeth, and the spring wells up. Kabir says: “Listen to me, my Friend! My beloved Lord is within.” O How may I ever express that secret word? O how can I say He is not like this, and He is like that? If I say that He is within me, the universe is ashamed: If I say that He is without me, it is falsehood. He makes the inner and the outer worlds to be indivisibly one; The conscious and the unconscious, both are His footstools. He is neither manifest nor hidden, He is neither revealed nor unrevealed: There are no words to tell that which He is. To Thee Thou hast drawn my love, O Fakir! I was sleeping in my own chamber, and Thou didst awaken me; striking me with Thy voice, O Fakir! I was drowning in the deeps of the ocean of this world, and Thou didst save me: upholding me with Thine arm, O Fakir!Only one word and no second– and Thou hast made me tear off all my bonds, O Fakir! Kabir says, “Thou hast united Thy heart to my heart, O Fakir!”

I played day and night with my comrades, and now I am greatly afraid.

So high is my Lord’s palace, my heart trembles to mount its stairs: yet I must not be shy, if I would enjoy His love.

My heart must cleave to my Lover; I must withdraw my veil, and meet Him with all my body:

Mine eyes must perform the ceremony of the lamps of love.

Kabir says: “Listen to me, friend: he understands who loves.

If you feel not love’s longing for your Beloved One, it is vain to adorn your body,

vain to put unguent on your eyelids.”

Tell me, O Swan, your ancient tale.From what land do you come, O Swan?

to what shore will you fly?

Where would you take your rest, O Swan, and what do you seek?

Even this morning, O Swan, awake, arise, follow me!

There is a land where no doubt nor sorrow have rule: where the terror of Death is no more.

There the woods of spring are a-bloom, and the fragrant scent “He is I” is borne on the wind:

There the bee of the heart is deeply immersed, and desires no other joy.

O Lord Increate, who will serve Thee?

Every votary offers his worship to the God of his own creation: each day he receives service–

None seek Him, the Perfect: Brahma, the Indivisible Lord.

They believe in ten Avatars; but no Avatar can be the Infinite Spirit, for he suffers the results of his deeds:

The Supreme One must be other than this.

The Yogi, the Sanyasi, the Ascetics, are disputing one with another:

Kabir says, “O brother! he who has seen that radiance of love, he is saved.”

The river and its waves are onesurf: where is the difference between the river and its waves?

When the wave rises, it is the water; and when it falls, it is the same water again.

Tell me, Sir, where is the distinction?

Because it has been named as wave, shall it no longer be considered as water?

Within the Supreme Brahma, the worlds are being told like beads:

Look upon that rosary with the eyes of wisdom.

Where Spring, the lord of the seasons, reigneth, there the Unstruck Music sounds of itself,

There the streams of light flow in all directions;

Few are the men who can cross to that shore!

There, where millions of Krishnas stand with hands folded,

Where millions of Vishnus bow their heads,Where millions of Brahmas are reading the Vedas,

Where millions of Shivas are lost in contemplation,

Where millions of Indras dwell in the sky,

Where the demi-gods and the munis are unnumbered,

Where millions of Saraswatis, Goddess of Music, play on the vina–

There is my Lord self-revealed: and the scent of sandal and flowers dwells in those deeps.

Between the poles of the conscious and the unconscious, there has the mind made a swing:

Thereon hang all beings and all worlds, and that swing never ceases its sway.

Millions of beings are there: the sun and the moon in their courses are there:

Millions of ages pass, and the swing goes on.

All swing! the sky and the earth and the air and the water; and the Lord Himself taking form:

And the sight of this has made Kabir a servant.

The light of the sun, the moon, and the stars shines bright:

The melody of love swells forth, and the rhythm of love’s detachment beats the time.

Day and night, the chorus of music fills the heavens;

and Kabir says”My Beloved One gleams like the lightning flash in the sky.”

Do you know how the moments perform their adoration?

Waving its row of lamps, the universe sings in worship day and night,

There are the hidden banner and the secret canopy:

There the sound of the unseen bells is heard.

Kabir says: “There adoration never ceases; there the Lord of the Universe sitteth on His throne.”

The whole world does its works and commits its errors: but few are the lovers who know the Beloved.

The devout seeker is he who mingles in his heart the double currents of love and detachment,

like the mingling of the streams of Ganges and Jumna;In his heart the sacred water flows day and night;

and thus the round of births and deaths is brought to an end.

*

Behold what wonderful rest is in the Supreme Spirit!

and he enjoys it, who makes himself meet for it.

Held by the cords of love,

the swing of the Ocean of Joy sways to and fro;

and a mighty sound breaks forth in song.

See what a lotus blooms there without water!

and Kabir says “My heart’s bee drinks its nectar.”

What a wonderful lotus it is,

that blooms at the heart of the spinning wheel of the universe!

Only a few pure souls know of its true delight.

Music is all around it, and there the heart partakes of the joy

of the Infinite Sea.

Kabir says: “Dive thou into that Ocean of sweetness:

thus let all errors of life and of death flee away.”

Behold how the thirst of the five senses is quenched there!

and the three forms of misery are no more!

Kabir says: “It is the sport of the Unattainable One:

look within, and behold how the moon-beams

of that Hidden One shine in you.”

There falls the rhythmic beat of life and death:

Rapture wells forth, and all space is radiant with light.

There the Unstruck Music is sounded;

it is the music of the love of the three worlds.

There millions of lamps of sun and of moon are burning;

There the drum beats, and the lover swings in play.

There love-songs resound, and light rains in showers;

and the worshipper is entranced in the taste of the heavenly nectar.

Look upon life and death;

there is no separation between them,

The right hand and the left hand are one and the same.

Kabir says: “There the wise man is speechless;

for this truth may never be found in Vadas or in books.”

I have had my Seat on the Self-poised One,

I have drunk of the Cup of the Ineffable,

I have found the Key of the Mystery,

I have reached the Root of Union.

Travelling by no track,

I have come to the Sorrowless Land:

very easily has the mercy of the great Lord come upon me.

They have sung of Him as infinite and unattainable:

but I in my meditations have seen Him without sight.

That is indeed the sorrowless land,

and none know the path that leads there:

Only he who is on that path has surely transcended all sorrow.

Wonderful is that land of rest, to which no merit can win;

It is the wise who has seen it,

it is the wise who has sung of it.

This is the Ultimate Word:

but can any express its marvellous savour?

He who has savoured it once,

he knows what joy it can give.

Kabir says: “Knowing it, the ignorant man becomes wise,

and the wise man becomes speechless and silent,

The worshipper is utterly inebriated,

His wisdom and his detachment are made perfect;

He drinks from the cup of the inbreathings

and the outbreathings of love.”

There the whole sky is filled with sound,

and there that music is made without fingers and without strings;

There the game of pleasure and pain does not cease.

Kabir says: “If you merge your life in the Ocean of Life,

you will find your life in the Supreme Land of Bliss.”

What a frenzy of ecstasy there is in every hour! and the

worshipper is pressing out and drinking the essence of the

hours: he lives in the life of Brahma.

I speak truth, for I have accepted truth in life;

I am now attached to truth, I have swept all tinsel away.

Kabir says: “Thus is the worshipper set free from fear;

thus have all errors of life and of death left him.” There the sky is filled with music: There it rains nectar: There the harp-strings jingle, and there the drums beat. What a secret splendour is there, in the mansion of the sky! There no mention is made of the rising and the setting of the sun; In the ocean of manifestation, which is the light of love, day and night are felt to be one. Joy for ever, no sorrow,–no struggle! There have I seen joy filled to the brim, perfection of joy; No place for error is there. Kabir says: “There have I witnessed the sport of One Bliss!” I have known in my body the sport of the universe: I have escaped from the error of this world.. The inward and the outward are become as one sky, the Infinite and the finite are united: I am drunken with the sight of this All! This Light of Thine fulfils the universe: the lamp of love that burns on the salver of knowledge. Kabir says: “There error cannot enter, and the conflict of life and death is felt no more.” —

[?]= unable to transliterate Sanskrit or Arabic characters

![[cmx] wait for it](https://moon-soup.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/cmx-wait-for-it.gif?w=500&h=217)